Deaf Māori face exclusion from their whānau and cultural heritage due to an extreme shortage of trilingual interpreters.

Imagine being deaf and at the tangi of a loved one. You stand when everyone else stands, sit when everyone else sits, and stare at the lips of speakers, trying to catch even a fragment of what they’re saying. You see laughter, you see tears, but you have no idea why.

Or picture being a deaf child at a kura kaupapa Māori, watching other children laughing and engaging, with the Māori words on the whiteboard and paper in front of you bringing no clarity. You do your best to follow along, but the songs, games, and conversations are out of reach.

Now imagine an interpreter was there, helping you understand what’s happening. You could join in the kōrero at the tangi, connecting with your whānau and heritage. At kura, words would come alive, expanding your vocabulary and deepening your cultural understanding. You’d be able to participate fully, forming connections and following lessons.

Unfortunately, for many deaf Māori, there are no interpreters in these settings. A severe shortage of trilingual reo Māori interpreters is preventing turi Māori from fully engaging in te ao Māori, robbing them of cultural identity and belonging.

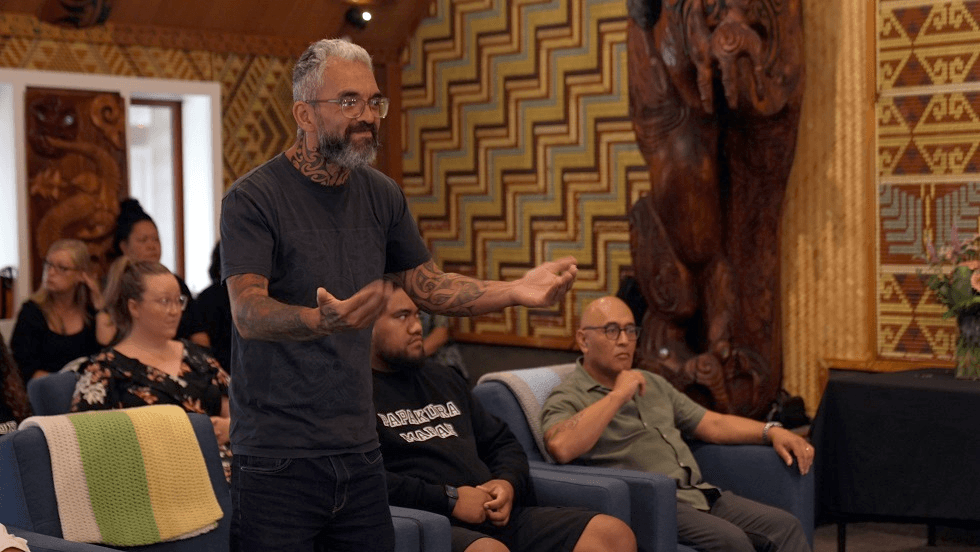

“It’s lonely. They feel isolated. They’re missing out on who they are as Māori,” says Jared Flitcroft (Ngāti Maniapoto), director of Being Turi, a recently released series highlighting the plight of tāngata turi.

The cultural significance of language

The journey of te reo Māori has been well documented – it flourished before colonisation, was brutally suppressed, and is now being revived. Understanding cultural concepts can be nearly impossible without some grasp of the language. Learning a language provides insight into its culture, but what happens when you are prevented from learning the language?

“Sometimes, the deaf whānau say hearing [people] have taken away their mana, or taken away their wairua,” Flitcroft says.

Seven years ago, I spoke to then-minister of Māori affairs Te Ururoa Flavell, who was using only te reo Māori for a year. Reflecting on the link between language and culture, he said, “Ko te reo te matapihi i te ao Māori – The language is the window into understanding and seeing the Māori worldview.” He explained that without understanding te reo, one misses a vital connection to the cultural depth of experiences like tangi and tikanga Māori.

A critical shortage

It’s impossible to discuss trilingual reo Māori interpreters without mentioning Stephanie Awheto, widely recognised as the country’s first trilingual interpreter. Her passing earlier this year left a significant gap in the turi Māori community. Awheto dedicated her life to advocating for turi Māori and developing the next generation of trilingual interpreters.

The National Foundation for the Deaf estimates around 880,000 New Zealanders are affected by hearing loss. About 4,600 people use sign language as their primary communication, and 23,000, including the whānau of deaf people, use some sign language. Yet, there are only 120 certified sign language interpreters in Aotearoa – one for every 38 tāngata turi. According to Deaf Aotearoa chief executive Lachlan Keating, fewer than a dozen of these interpreters can translate both te reo Māori and New Zealand Sign Language. For Pacific Island languages, the number is even smaller.

While not every deaf person needs interpreting services daily, trilingual interpreters are essential for events like kura lessons or cultural gatherings, where they’re often booked well in advance and rarely available for last-minute kaupapa like a tangi following a sudden death.

“There are certainly not enough interpreters to ensure that deaf people have the same access as hearing people to life and everyday things,” says Keating.

Cultural disconnect and lack of access

Beyond the shortage, deaf Māori may not even request interpreters for events where there’s no history of their presence. As Keating explains, they might avoid attending a tangi or marae gathering, saying, “I won’t go because I can’t access, I won’t know what’s going on, so I won’t bother going.”

This isolation often leaves turi Māori questioning their identity. While some, like Flitcroft, reconnect with their culture later in life, he stresses the importance of early support to prevent lifelong barriers. Young deaf Māori need access to interpreters and culturally relevant resources to fully engage with te ao Māori.

“I know people say it’s never too late to learn, but that’s bullshit – especially for young Māori who are deaf. This lack of inclusion holds them back, and they end up relying on others or blaming the hearing. We need a plan to address their needs and ensure future generations aren’t left out,” Flitcroft says.

The path to inclusive education

For deaf students in Māori education, there is a pressing need for culturally aligned support, including NZSL resources that reflect Māori contexts. Resources like visual aids, hands-on learning, and accommodation for practices like pōwhiri and kapa haka are essential but lacking.

Compounding the accessibility issue is that interpreter services are billed hourly. Public institutions and state-owned organisations that offer education or training, such as NZ Police Training Services and the New Zealand Army, are required to provide interpreters for no cost to the user, but this can still require lengthy advocacy and effort to ensure an interpreter is available. It’s even more difficult when it comes to private institutions and events, further restricting access to necessary services.

“I would expect that government contracts with training providers clearly require all courses to be accessible to everyone, including deaf and disabled individuals. Just as a ramp or elevator would be installed for wheelchair users, interpreters should be provided for deaf people who wish to pursue training and education,” Keating says.

The way forward

For Keating, addressing the lack of trilingual interpreters is essential. He emphasises that without a pipeline of new interpreters and adequate funding, it’s unlikely the situation will improve. While agencies like the Ministry of Disabled People and the Ministry of Education advocate for better access, without meaningful financial support, it is unclear how the interpreting workforce will grow to meet these needs.

“Money is the key – policies alone won’t cut it,” says Keating.

Flitcroft also calls on whānau of turi Māori to increase their support. Hearing families often delay learning sign language, citing time constraints, yet early access to sign language is critical for a deaf child’s development. Basic signs from infancy can create a foundation and groups like Plunket could play a vital role in encouraging whānau to learn early. Consistent sign language interactions at school and home foster a sense of belonging and confidence.

“Deaf children will always be deaf; they won’t just become hearing. It’s about giving them a real sense of belonging and confidence, not trying to ‘fix’ their deafness,” Flitcroft says.

Recently, I attended a reo Māori symposium that thoughtfully accommodated whānau turi. Though not perfect, the organisers were responsive to the needs of the turi attendees, allowing them to participate fully – benefitting everyone involved. Thanks to advocates like Flitcroft, Aotearoa is becoming more aware of the challenges turi Māori face, but there appears to still be a long road ahead to creating a fully inclusive society.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.

Discussion about this post